In part one, we looked at the bikes that initially participated in the Tour and how brakes, freewheel and gear shifting gradually appeared in their design. In our second article, we are going to take a leap in time right to the 1990s and the early 2000s, when the greatest changes in materials and bike designs took place. Hold on, the curves are about to come, just like in Alpe D’Huez.

The farewell to steel, the transitory aluminum and the advent of carbon

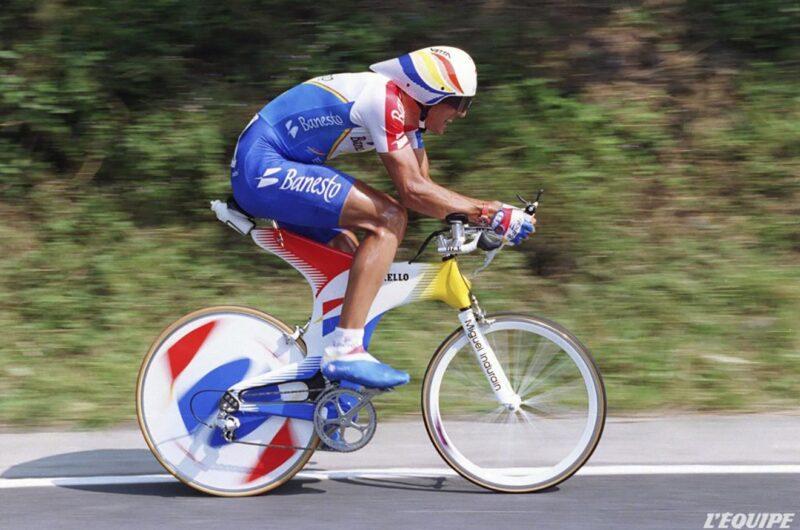

Miguel Indurain’s fourth Tour riding Pinarello in 1994 was the last one to be won on a steel bike. At the end of the 1980s, with the victories of Greg LeMond and Pedro Delgado, we saw the appearance of the two materials that would mark the years to come: aluminum and carbon. However, it was not until Indurain’s fifth and last Tour in 1995 that steel began to disappear. His Pinarello model that year was made of aluminum, and so were all the winning bikes until Lance Armstrong’s first Tour. Among them, Marco Pantani’s beautiful Bianchi Mega Pro XL Reparto Corse that ended the dominance of Pinarello during those years.

In 1999 the American won the first of his seven Tours. Although we already know how it all ended, the American’s Trek 5200 marked two milestones: it was the first 100% carbon bike to win the Tour and it meant the first victory for Shimano, the Japanese manufacturer of bike components. Since then, Shimano have only failed to win on 6 occasions (4 times against Campagnolo and 2 against Sram) and today it is the brand used by the vast majority of World Tour teams. Besides, the construction of Trek itself was a novelty as it was the first bike not manufactured using traditional methods (tubes joined by welding or lugs), but instead came out of a mold like the vast majority of current carbon bikes.

The yellow jersey gives you wings, but aerodynamics makes you fly

For today’s generations, Pogačar’s comeback over Roglič in the individual time trial on the second to last day of the 2020 Tour was a huge surprise; but what American Greg LeMond did in the ITT on the last day of the ’89 Tour on the Champs Elysees, with more than half the world watching and with all of France waiting to see Frenchman Laurent Fignon celebrate the victory, was not only a history-making moment for winning the Tour with the smallest margin, but also the first proof of the importance of aerodynamics.

Although plenty has been written and debated about the final outcome of that Tour, the fact is that Fignon was 50 seconds ahead of LeMond before the 24.5 km time trial and at the end of the day he was 8 seconds behind the American, seeing him raise his arms in the yellow jersey on the Champs Elysees. LeMond beat him by 58 seconds, 2.3 seconds per km, riding at 2 km/h more on average than Fignon. It’s true: LeMond was better at time trial, but then why didn’t Fignon use the same (or similar) handlebars as the American, why didn’t he wear a helmet and different cycling glasses instead of riding with his hair pulled back in a ponytail and glasses with high air resistance? He can’t say he was caught by surprise and didn’t have time to look for alternatives and test them out. LeMond had already used the triathlon handlebars and aero helmet in the previous time trial stages of that Tour. Fignon simply didn’t bother, and once he did, two months later in the Grand Prix des Nations, he was unstoppable.

Aerodynamics applied to cycling was there to stay for good together with some very radical and groundbreaking designs on the bikes and time trial equipment of the 1990s. It lasted until 2000, when the UCI set very strict rules for bikes and equipment. It was the end for Pinarello Espada (Indurain’s bike) or Lotus (Chris Boardman’s bike) that you could see in the photos in the first part of the article on Tour de France bikes history.

We have to go back to 2003 and the Cervélo Soloist model from Team CSC to see the first regular road bike featuring an aero concept in the Tour de France. The name of the bike spoke for itself. An aluminum bike with flat rather than round frame tubes, designed to be as aerodynamic as possible and to offer additional “advantages” to the rider when riding solo. What was then considered a very specific design for certain circumstances or stages has now become standard on all Tour teams’ bicycles.

Changing geometry

Finally, something that may seem minor, but it is quite the opposite: bike geometry. The design of the two triangles and the fork means that there are angles and measurements that affect the performance and reactions of the bike as much as the material it is made of or even more. However, the material together with the technology and components available at the time, also determine the final shape and design of the bike.

If we compare the 1903 bike with the 2021 bike, we will see that Maurice Garin’s bike has an approximately 1.2 m wheelbase, a tighter head tube angle and fork rake further forward. It is designed to absorb road shocks, be stable and easy to ride. The Colnago on the other hand, with around 1 m wheelbase, a 73° head tube angle and minimal fork rake, is designed to be agile and transmit every watt of power coming from Pogačar’s legs.

The first change occurred in the bicycles at the end of the 30s (in the picture above, you can see the Legnano of Bartali, winner of the 1938 Tour). Around this time, the two triangles became smaller and the wheelbase was reduced. Roads, materials, components and bicycle manufacturing technology improved to some extent. The change in angles and sizes became even more noticeable post-war. Below, you can see the Bianchi on which Coppi won the 1949 Tour.

The geometry changes between the Coppi’s Bianchi and Pantani’s Bianchi from 1998 are minimal, but a year later the Giant TCR (Total Compact Road) made its Tour debut with the ONCE team.

A bike by one of the most important bike designers in history, Mike Burrows, inspired by mountain biking to develop a groundbreaking idea compared to what was on the road bike market at the time. It is much more compact, with the distinctive sloping on the top tube that reduces the size of the main triangle. The rear triangle is also smaller, with very short chainstays and seat stays that attach to the seat tube below the top tube. All this allows for reduced weight, more stiffness, better handling, as well as more balanced frames for shorter people.

The design from 1997 was so groundbreaking that Giant still has the TCR model in their catalog to this day. It has been aesthetically and technologically updated to keep up with the latest innovations, but many of the bikes we see today at the Tour de France are clearly inspired by the Burrows design. What will be the next big thing? We may already be experiencing one: the introduction of disc brakes; however, the strict UCI regulations don’t leave much room for innovation either. In other words, the world governing body for cycling is acting like Henri Desgrange in those early editions of the Tour de France.

Great articles on bike evolution! Realy enjoyed reading about all the changes over time

Hi Paul,

Thanks loads for reading our blog!

Best

You forgot to mention that Oscar Pereiro won the 2006 Tour aboard a Pinarello Dogma made of magnesium, the Dogma FP Ak61. It was the last metal frame to win the Tour.

Hi David,

You’re right, but we wanted to focus on the most important materials of the Tour de France bikes: steel, aluminium and carbon. Even Oscar Pereiro’s Pinarello has a carbon fork and carbon seat stays.

Thanks for reading our blog and commenting.

Best

Excellent article, great research and very informative pieces

Hi Shaun,

Thanks loads for reading our blog!

Best

Pingback: What Bike Did Lance Armstrong Ride - eBikeAI

Pingback: Tour De France Team Bikes - eBikeAI